Issue 12: Seven Generations vs. Four-Year Terms: Indigenous Approaches to Policymaking

Plus, a "public acceptability" tool and a reality check on think tank careers

WELCOME

Before we get to the meat of the newsletter, just a quick reminder about Policycraft: The Implementation Phase (a.k.a. a casual meet-up in Toronto next week). Hope to see some of you there!

Indigenous Approaches to Policymaking: An Exploration and Invitation

This month’s edition of Policycraft is structured a bit differently, as I want to invite you into my process and see if we can learn together. I’ve been exploring Canadian First Nations approaches to policymaking for some time, finding myself navigating what appears to be a notable gap in the literature. While Indigenous scholars have produced rich legal analyses of sovereignty and rights, there’s surprisingly limited writing that directly addresses the art of policymaking through an Indigenous lens. Below, I’ve shared some of what I’ve learned so far, but would like to invite my readers to contribute their own insights and offer their own resources as part of an evolving conversation, either in the comments or directly with me.

THIS MONTH’S SYLLABUS

The natural starting place for this exploration is the “seven generations” concept: the principle that decisions should consider their impact seven generations into the future. Influential legal scholar John Borrows offers a particularly helpful articulation of this philosophy in his piece for the National Centre for First Nations Governance, where he weaves together the seven generations concept with the seven grandfather teachings (wisdom, love, respect, bravery, humility, honesty, and truth) to imagine governance beyond the Indian Act. His work demonstrates how traditional teachings can inform contemporary governance challenges while maintaining cultural integrity.

Some international scholarship can offer complementary perspectives, particularly work coming out of Australia. A common thread is how, by excluding Indigenous ways of ‘knowing’ (including knowledge-generation/collection), critical information is left out of policymaking, thus undermining its efficacy.

Back in Canada, one scholar has proposed to adapt the established Indigenous Research Framework into an Indigenous Policy Research Framework. This approach addresses how policy studies have been complicit in maintaining colonial knowledge production practices in relation to Indigenous peoples, and proposes principles for ‘decolonizing’ policy research.

Ethnographic research can provide ground-level insights into how these principles operate in practice. The University of Victoria’s Indigenous Governance Program is producing such work, including this MA thesis examining the policymaking values of an Indigenous civic organization, the Bent Arrow Traditional Healing Society in Edmonton. Bent Arrow’s governance model demonstrates how traditional teachings - including the Medicine Wheel and Natural Laws of love/kindness, honesty, sharing, and strength - can structure contemporary service delivery. Their approach is also illustrative of how Indigenous policymaking values frequently emerge from lived practice rather than abstract theory.

Beyond the environmental and natural resource extraction policies that tend to dominate much Indigenous policy discourse, First Nations are asserting control over fundamental aspects of governance that the Indian Act has historically constrained. Take, for example, data sovereignty. The principles of OCAP (ownership, control, access, and possession) establish how First Nations’ data and information will be collected, protected, used, or shared - supporting strong information governance as a means to data sovereignty.

What I’ve understood from this incomplete review is how Indigenous policymaking approaches consistently emphasize relationships, reciprocity, and long-term thinking over a transactional, short-term orientation. These aren’t simply different methods for achieving similar ends; arguably, they represent fundamentally different understandings of what policy is for and how it should function in society.

I invite readers who have encountered other examples of Indigenous policymaking frameworks - whether from Canada or elsewhere, in scholarship or in practice - to share their findings. I’m particularly interested in work that bridges the theoretical and practical, showing how Indigenous knowledge systems translate into concrete policy mechanisms and outcomes.

📚 “Introduction: The Concept of Policy Style” by Jeremy Richardson in British Policy-Making and the Need for a Post-Brexit Policy Style*

Attempting to understand the differences between non-Indigenous Canadian forms of policymaking and that of First Nations governments naturally raises the question of how policymaking is approached in different national or cultural contexts. Comparative policy analysis is a well-established form of scholarship, and many readers may have likely encountered Jeremy Richardson’s name from a notable 1982 work comparing policy styles in Western European countries. Here, in the introduction to his 2018 book, he re-visits his analysis of the British policy style and traces how it has seemingly calloused in recent years. A worthwhile read as we reflect on how policy styles have evolved in the past - and so may be capable of change in the future.

*NB: Rather than directing you to purchase this book in order to read the introduction, I’m sharing a PDF’d version of the unproofed draft helpfully posted by the author on his ResearchGate profile (a.k.a. the academic’s PirateBay).

🎓 “Anticipating and designing for policy effectiveness” by Azad Singh Bali, Giliberto Capano & M. Ramesh, Policy and Society

Good policy design isn’t merely about choosing the right tools, it’s about anticipating how those tools will perform in the real world. This paper argues that effective policies require anticipating their appropriateness along three dimensions: analytical (can the instrument solve the problem?), operational (is it feasible to deploy?), and political (is it acceptable to the public?). The authors apply this lens to both the choice of policy instruments and the capacity of implementing agencies, making the case that anticipation (foreseeing the future and preparing for it) should be central to how policies are designed, executed, and assessed.

💻 Getting the Public on Side, OECD

This recent report from the OECD tackles a challenge every policy professional knows well: building public support for necessary reforms. The outcome of their research is a Public Acceptability Tool to help policymakers more accurately assess whether proposed reforms align with public perceptions. For Canadian policy thinkers navigating everything from climate change to health system reform, this offers a practical framework for integrating public acceptability into the policymaking process from the start.

💻 Reasons not to work at think tanks, by Joe Hill, Re:State

In a refreshingly honest recruitment pitch, Re:State’s Policy Director flips the script on think tank job advertisements by laying out all the reasons you shouldn’t apply to his organization. From the reality that you’ll need to argue unpopular positions publicly to the fact that salaries can be modest, this piece cuts through the usual “intellectually stimulating” platitudes to describe what the work actually entails. Consider this a valuable gut check on whether the sector’s realities match your expectations.

(Personally, I loved working at a think tank, and so wish Canada’s ecosystem was larger and more robust, particularly for early-career researchers and wonks who would benefit from the wealth of learning opportunities afforded by this kind of workplace.)

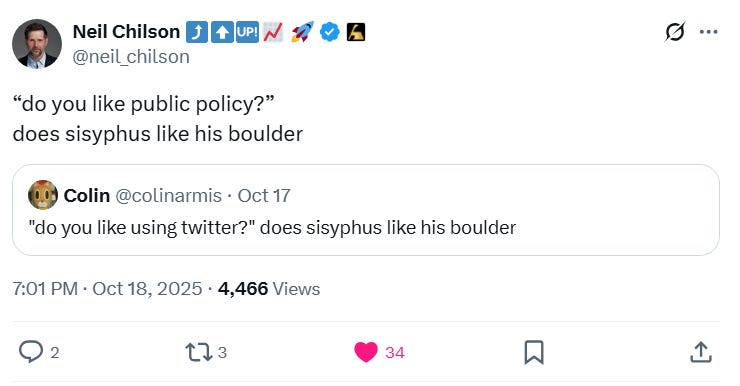

📣 “Do you like public policy?” social post by Neil Chilson, Twitter/X

Sigh.